So you want to learn to read chord symbols.

It’s not easy. And it’s not hard. It all depends on how well you know the major scale, really. And the style of music.

Major scale

This page more or less presumes you already know what a major scale is. Since it’s in the previous chapters. But here’s a short recap. Just to be sure we’re thinking of the same scale.

It’s a sequence of 7 unique tones with the following distances (intervals) between them (legend: whole tone/major second = whole, semitone/minor second = semi):

‘Starting tone’ (= tonic = point of reference: in the major scale of C it’s ‘c’) and then upwards – increasing in pitch (frequency);

whole – whole – semi –

whole – whole – whole – semi;

at which point we’ve reached the ‘starting tone’, only one octave higher.

The major scale is best known as ‘do-re-mi-fa-so-la-ti-do’ and sounds like this…

Numbers

A major scale has 7 unique tones. The major scale of C: c,d,e,f,g,a,b. Numbering them in order results in this:

- c = 1

- d = 2

- e = 3

- f = 4

- g = 5

- a = 6

- b = 7

The numbers in chord symbols are always (!) based on the major scale.

Second octave

The ‘c’ on which the scale would end – one octave up from the ‘c’ with which we started – becomes number 8. Numbers continue into the second octave. All numbers from the first octave +7:

- c = 8

- d = 9

- e = 10

- f = 11

- g = 12

- a = 13

- b = 14

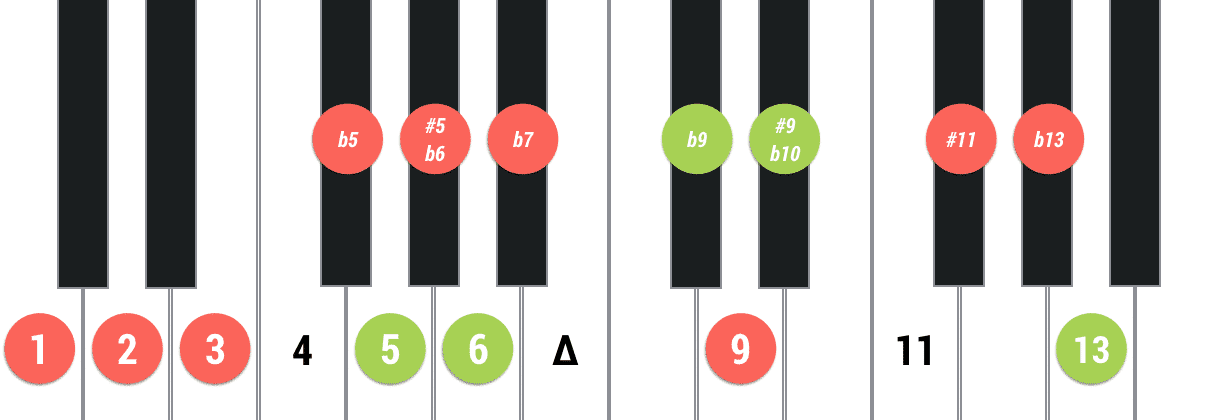

Not all numbers from the second octave are used in chord symbols. Simply because they don’t match or they are the same tones as the ones in the first octave. These are the most frequently used numbers as they would be from ‘c’ on a piano keyboard.

Chords

Chords consist of 3 different tones minimal and usually, they are the 1, 3 and 5. These 3-tone chords are known as triads. And they come in several different ‘flavors’.

The accidentals b (flat = lowers a tone by a semitone) and # (sharp = raises a tone by a semitone) are used in chord symbols as well. Only not in front of notes but numbers.

- 3 = the third tone of the major scale;

- b3 = a semitone lower than the third tone of the major scale;

- b5 = a semitone lower than the fifth tone of the major scale;

- #5 = a semitone higher than dan the fifth tone of the major scale.

Major = 1,3,5

Minor = 1,b3,5

Diminished = 1,b3,b5

Augmented = 1,3,#5

The capital letter in chord symbols represents the 1 of the triad: the point of reference.

And it can be accompanied by an accidental (b or #) behind the capital letter (!) to indicate it’s not a ‘b’ (B) but a ‘b flat’ (Bb) for example. Orf C# = ‘c sharp’.

We’ll be looking at the different types of triads and their symbols. But first this…

Although you might be used to music notation with notes they are not used here.

It’s the best way to get used to making music without notes :)

TIP

If you want to become a skilled reader of chord symbols you have to make sure you know the major scale by heart in all 12 keys.

Not just in order. You have to instantly be able to name “the 6th tone of the major scale of C” for example.

Chill, relax!

Music theory isn’t entertainment. But it will enable you to have lots of fun later.

Major triad

If there’s a capital letter – possibly with a b or # behind it – it indicates a major triad (1,3,5).

- Bb = 1,3,5 of the major scale of Bb: b flat,d,f;

- C = 1,3,5 of the major scale of C: c,e,g;

- F# = 1,3,5 of the major scale of F#: f sharp,a sharp,c sharp.

Minor triad

If there’s a line (-), ‘m’ or ‘min’ or ‘minor’ behind the capital letter – possibly with a b or # behind it – it indicates a minor triad (1,b3,5).

- Bbm = 1,b3,5 of the major scale of Bb: b flat,d flat,f;

- C min = 1,b3,5 of the major scale of C: c,es,g;

- F#- = 1,b3,5 of the major scale of F#: f sharp,a,c sharp.

Diminished triad

If there’s a circle (o) or ‘dim’ behind the capital letter – possibly with a b or # behind it – it indicates a diminished triad (1,b3,b5).

- Bbo = 1,b3,b5 of the major scale of Bb: b flat,d flat,f flat(e);

- C dim = 1,b3,b5 of the major scale of C: c,e flat,g flat;

- F#o = 1,b3,b5 of the major scale of F#: f sharp,a,c.

Augmented triad

If there’s a plus (+), ‘aug’ or ‘#5’ behind the capital letter – possibly with a b or # behind it – it indicates an augmented triad (1,3,#5).

- Bb+ = 1,3,#5 of the major scale of Bb: b flat,d,f sharp;

- C aug= 1,3,#5 of the major scale of C: c,e,g sharp;

- F# #5 = 1,3,#5 of the major scale of F#: f sharp,a sharp,c double sharp(d).

Suspended

If there’s ‘sus’ or ‘sus4‘ behind the capital letter – possibly with a b or # behind it – it indicates a triad with a 4 instead of a (b)3 (1,4,5). The 4 suspends the (b)3.

- Bb sus = 1,4,5 of the major scale of Bb: b flat,e flat,f;

- C sus4 = 1,4,5 of the major scale of C: c,f,g;

- F# sus4 = 1,4,5 of the major scale of F#: f sharp,b,c sharp.

If there’s ‘sus2‘ behind the capital letter – possibly with a b or # behind it – it indicates a triad with a 2 instead of a (b)3 (1,2,5). The 2 suspends the (b)3.

- Bb sus2 = 1,2,5 of the major scale of Bb: b flat,c,f;

- C sus2 = 1,2,5 of the major scale of C: c,d,g;

- F# sus2 = 1,2,5 of the major scale of F#: f sharp,g sharp,c sharp.

6

If there’s a ‘6’ behind the capital letter – possibly with a b or # behind it – it indicates a major triad (1,3,5) with the 6th tone of the major scale.

- Bb6 = 1,3,5,6 of the major scale of Bb: b flat,d,f,g;

- C6 = 1,3,5,6 of the major scale of C: c,e,g,a;

- F#6 = 1,3,5,6 of the major scale of F#: f sharp,a sharp,c sharp,d sharp.

7

If there’s a ‘7’ behind the capital letter – possibly with a b or # behind it – it indicates a major triad (1,3,5) with a semitone lower than the 7th tone of the major scale. A b7 in fact. Because this was the first ever 7 used in chords the notation of the b7 became ‘just’ 7.

- Bb7 = 1,3,5,b7 of the major scale of Bb: b flat,d,f,a flat;

- C7 = 1,3,5,b7 of the major scale of C: c,e,g,b flat;

- F#7 = 1,3,5,b7 of the major scale of F#: f sharp,a sharp,c sharp,e.

∆

If there’s a triangle (∆), ‘M7’, ‘maj7’ or ‘major7’ behind the capital letter – possibly with a b or # behind it – it does indicate a major triad (1,3,5) with the 7th tone of the major scale.

- Bb∆ = 1,3,5,7 of the major scale of Bb: b flat,d,f,a;

- C maj7 = 1,3,5,7 of the major scale of C: c,e,g,b;

- F# M7 = 1,3,5,7 of the major scale of F#: f sharp,a sharp,c sharp,e sharp(f).

Combinations

All this means you can encounter any kind of triad with any kind of additional tones.

- Bbm6 = 1,b3,5,6 of the major scale of Bb: b flat,d flat,f,g;

- C+ 7 = 1,3,#5,b7 of the major scale of C: c,e,g sharp,b flat;

- F#m∆ = 1,b3,5,7 of the major scale of F#: f sharp,a,c sharp,e sharp(f).

Diminished notations

Two kinds of diminished triads (1,b3,b5) with a 7 (which is a b7 in principle) are different or notated differently.

Cm7 b5, Cø or Cø7 (also known as half-diminished) = 1,b3,b5,b7 of the major scale of C: c,e flat,g flat,b flat;

Co7 or C dim7 = 1,b3,b5,bb7 (!) of the major scale of C: c,e flat,g flat,b double flat(a).

Slash

‘Slash chords’ are chords with an alternative bass note. Not optional but meant to be used as the lowest tone of the chord instead of the 1.

Such a small change to the lowest tone of a chord has a huge impact on both sound and function of the chord. The lowest tone is the point of reference of which the value/meaning of all other chord tones is based.

The alternative bass note is notated behind the complete chord symbol (including numbers and such) with a diagonal line first (/) followed by the alternative bass note indicated by a capital letter with the optional b or #.

C/E (pronounced C with an ‘e’ in the bass) is not a C major triad with an E major triad beneath, but a C major triad with an ‘e’ in the bass (as lowest tone).

C = c,e,g

C/E = e,g,c or e,c,g – as long as ‘e’ is the lowest tone.

Beyond the 7

Numbers beyond 7 are kind of rare in chord symbols.

Most frequently used in harmonically – harmony is multiple tones sounding simultaneous like in chords – complex styles like Jazz and related styles like Fusion and Bossa Nova.

Because of a lack of uniformity, it’s more a matter of remembering definitions than logic. It’s because the most frequently used combinations are favored.

It’s near impossible to be fully complete. So many different notations are used. And views differ on their meaning as well. So it’s also near impossible to be 100% accurate. But this will get you to 97,564%.

For the remaining 2,437% the Creator or evolution if you wish has given you two shell-like appendices glued to your head. They are commonly known as ears. It’s highly recommended using them when being involved with music :)

9

The 9 is basically the 2 yet in the second octave.

It’s sometimes added like this ‘add9‘. C add9 = 1,3,5,9 = c,e,g,d.

Sometimes it only reads ‘9‘. This means a major (or minor if indicated) triad with b7 as well as a 9. C9 = 1,3,5,b7,9 = c,e,g,b flat,d.

Sometimes the ‘9’ is added separated by a comma. C7,9 = 1,3,5,b7,9 = c,e,g,b flat,d.

b9 and #9 (the #9 sometimes replaced by b10) are added to chords separated by a comma. C7,b9 = 1,3,5,b7,b9 = c,e,g,b flat,d flat.

Well, a comma or just a space. Or the chord additions/extensions beyond 7 are higher up in smaller characters. Music is a universal language written and spoken differently by everyone :)

11

The 11 is mostly (modernist do all sorts of weird stuff) added to minor chords.

Separated by a comma for example. Cm7,11 = 1,b3,5,b7,11 = c,es,g,b flat,f.

Or as ‘11‘ meaning ‘7,9,11’. Cm11 = 1,b3,5,b7,9,11 = c,e flat,g,b flat,d,f.

The #11 is usually added to major chords. C7,#11 = 1,3,5,b7,#11 = c,e,g,b flat,f sharp.

b11 = 10.

13

The 13 and b13 are usually added after a space or a comma. C7,13 = 1,3,5,b7,13 = c,e,g,b flat,a.

When it’s just 13, like C13, C7,9,#11,13 is meant.

#13 = b7.

b13 = #5 which means no 5 is used in chords with a b13. C7,b13 = 1,3,b7,b13 = c,e,b flat,a flat.

add

Any tone can be added through ‘add’. C add4 = 1,3,4,5 = c,e,f,g. Just an unlikely example. It’s the principle that counts.

alt

Sometimes – mostly in Jazzzzzzzzzzz – you will encounter ‘alt’ in chord symbols. It’s a complex chord with an equally complex explanation. It means a chord with not only a b7, which is usually written in the symbol like this ‘7alt’. Not everyone agrees on the contents of ‘alt’ chords. The consensus is that these chord contain a b7, b9 as well as a #9 (b10), a #11 and a b13:

7,b9,b10,#11,b13. It will take some time in the beginning :)

Because of the b13 (=#5 yet with a downwards – b – direction instead of upwards – #) no 5 is used.

- Bb7alt = 1,3,b7,b9,b10,#11,b13 of the major scale of Bb: b flat,d,a flat,c flat(b),d flat(c sharp),e,g flat;

- C7alt = 1,3,b7,b9,b10,#11,b13 of the major scale of C: c,e,b flat,d flat,e flat(d sharp),f sharp,a flat;

- F#7alt = 1,3,b7,b9,b10,#11,b13 of the major scale of F#: f sharp,a sharp,e,g,a,c,d.

‘alt’ comes from ‘altered’; an understatement.

Order of the chord tones

You can place the chord tones when playing a chord instrument in any order as long as;

- there are no b9 intervals (distances) between the chord tones – except the one between 1 and b9 (if b9 is in the chord)*;

- the 1 or alternative bass note (‘slash chords’: chords with a /) is used as the lowest note – either by you or a bass instrument.

*unless you’re a ‘pro’ aiming to create something ‘weird’

Yes, every order has a unique sound.

- Semitone and whole tone intervals between chord tones sound full but too full for lower registers.

- Minor and major intervals between chord tones sound normal.

- Fourth and augmented fourth (#4) intervals between chord tones sound full even in the somewhat lower registers (the lower you go, the greater the distances between chord tones preferably).

- Fifth and sixth intervals sound transparent. Larger intervals become even more transparent in the higher registers – well suited for lower registers.

What does it mean?

Suppose, you encounter a C6,9 chord: c,e,g,a,d. You could ‘lay it down’ from bottom to top just like that on your instrument. Possibly leaving the bass (c) to the bass player if there is one.

But you could also choose for c,e,a,d,g: containing no less than three fourth intervals – full and open because of its larger ‘spread’.

Or choose c,d,e,g,a for example: compact and full with no less than three whole tone intervals in between both ‘c & d’, ‘d & e’ and ‘g & a’.

Try and experiment!

This ordering of chord tones is often called ‘voicing‘. ‘Voicing’ is in fact (just so you know) how chord tones form separate mini-melodies: second, third, fourth, etc. voices.

Meaning the ordering of chord tones of one chord determines the order in the next – in order to make smooth transitions.

Use

What now? You can read chord symbols – takes some practice, but you’ll get used to it. How to use them?

First: suppose you’re not very handy/quick yet in reading chord symbols.

As long as you hit the basic triad of the chord – 1,3,5 in whatever ‘flavor’ it comes – depends on the chord naturally- you have the essence of the chord.

If you can add the 6 or 7 – in whatever ‘flavor’ and only if they are written in the chord of course: great!

So if you can’t find those 9, 11 of 13 – in whatever ‘flavor’ and only if they are written in the chord – quick enough, focus on the essence of the chord.

Rhythm

You could just lay down the chord or play it rhythmically fitting the style.

Or you could play the chord tones separately – broken chords, also known as arpeggios – in a rhythm: usually in 4/4 beat you use the bottom 4 tones of the chord for example. When there are only three like in a major triad for example use 1,3,5,8. In 3/4 use the bottom three. That’s the basic concept. Be creative!

If you have to choose, leave out 5 (or b5 or #5) in favor of the b7 if one is in the chord: use 1,3 (or b3) and b7.

But suppose you still have some fingers left :)

Bass

You could make creative basslines. But…be extremely careful. The lowest tone is the point of reference that determines the value/sound/function of all other tones.

Here’s a good and safe starting point.

Use the 1 (or alternative bass note) and 5 (or b5 or #5).

The 1 on prominent/emphasized spots/beats (like the 1 of each measure for example). Use the 5 (or b5 or #5) ‘in between’.

Nothing wrong with using just the 1 (or alternative bass note). Better well ‘timed’ – ‘timing’ is the rhythmic placement of tones – than creative but badly timed. A good timing creates rest, a bad timing unrest/chaos. Up to you what you’d like to give your audience :)

Improvisation

Improvisation is everything you do musically that’s not written down by someone else (the composer or arranger).

How you interpret chord symbols – the order and placement of the chord tones you use – thus is improvisation.

The way you interpret melodies of themes as well if you don’t precisely stick to the notes.

Want to improvise over the chords – make your own melodies? It can be quite challenging. Which scales to use and much more theory on how chords are related to each other. You might be able to do it just by ear. But if you want to improvise ‘scat’ solos, that jazz thing, you’ll need more knowledge, ear training and exercises.

Luckily

Luckily I’ve made all the knowledge, ear training and exercises you need available through Songbird.

Better still. The course “How to improvise” contains the easiest way to learn how to improvise. All you need is knowledge of the chord symbol system. Which you now have. Better better better still: it can even be done just by ear with this system designed by Dutch jazz pianist and composer Erik van der Luijt. By the way, he’s my husband. And his improvising method comes recommended by iRealPro ©.